My first ballet teacher, Maud, was in her 60s and had intense grandmother vibes. She talked constantly about her beloved grandson, who always got perfect grades. She had never stopped using a record player, and while I waited in the hallway, I could hear the music she played for her jazz class: “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” and “Big Girls Don’t Cry.” Maud was both cozy and distinctive, venerable and very much herself. She had short, curly hair (possibly a perm), crepey skin under her chin, and a plump belly. She taught in an old T-shirt, plain black bottoms, and, always, fishnet tights.

I switched schools in eighth grade, starting classes at a dance studio dedicated to ballet. The teacher there took one look at me in class and saw through my claim to four years of dance education. “You have no technique,” she told me. I had been what they call “badly trained,” which is to say (ominously, always, these are ballet instructors after all), worse than having no training. To start at this studio, then, would be starting over.

The odds were not in my favor—I am not what anyone would call naturally gifted at dance. To start, I am extremely unrhythmic: my mom recalls watching me jump rope as a child, and I would sing the rhymes completely independent of the beat of the jump rope. I’m not very flexible, and I have a very stiff back, so I never had a very good arabesque or extensions. My turnout was mediocre. I tended to overpronate. Perhaps it was pigheadedness keeping from quitting ballet. On the other hand, I was no stranger to learning things from scratch.

It’s not quite correct, though, to say I was learning from scratch. I was learning something I had been doing the wrong way for years. I had to do just as much unlearning as learning, for a long time. It was starting from scratch and then some.

This was really hard. Ballet is a very technical dance form, and even simple things like sliding your foot out in front and pointing it (a tendu) takes a lot of effort to learn to correctly—more difficult or complex movements could accurately be described as grueling to practice. You have to learn how to engage muscles you were not even aware of. You have to learn a way of movement that is unintuitive and awkward—turning your legs out from the hip joint, for example, is a very strange thing to do. You start to understand your body in a minute way, like it’s made up of the tiniest nuts and bolts, and you learn to break down movements, understanding all the tiny choices you’ve made and directions you’ve taken before you even move, just while standing.

I wasn’t really doing school, as it were, but I was doing ballet six days a week. Discipline, training, technique—these were words I associated not with formal education, or writing, or even learning math, but with what I guess you could call my PE. It was by far the hardest work I had ever done.

Another odd thing about my ballet education: the experience had a largely positive effect on my self perception, including my relationship with my body. Ballet has a reputation for being run by a bunch of sadistic weirdos, weight-obsessed, and just generally toxic. The reason it has this reputation is because that’s how a lot of it is.1 For many people looking in, the grittiness and the toxicity, combined with the ethereal aesthetics, are the appeal—think Black Swan or Tiny Pretty Things.2

I started relearning ballet as a brainy, slightly out-of-it teenager, a little stuck in my head. Mainly I loved books, and I thought of art as the abstract stuff. My journals from this time are an interesting mix of withering scorn for everything I deemed bad literature3 (I constantly critiqued the introductions to my own diary entries) and breathless rhapsodies about the connections between beauty, art, and magic (?). That art could be something embodied had never really occurred to me. But ballet challenged how I thought about my body, so much so that I began to experience it differently.

By the time I started doing dance seriously, like many (perhaps most) adolescent girls, I had already had enough bad experiences to internalize the idea that there was something inherently dangerous about being a woman. It is a very difficult thing to come to the realization that not only are you particularly vulnerable to specific kinds of violence, but also that your very vulnerability is fetishized. I do not recommend the experience. I felt a lot of fear, and my body seemed like the source of the problem.

Ballet did not cure this. I don’t think anything will ever make that feeling go away completely. But it helped, and dance studios were essentially the only places where I was expected to be strong, to move as if I could command a room. I wouldn’t have put it this way then, but dance made me feel like I was in control, of my body and, to some extent, the space around me.4

My early days of working on technique gave me an understanding of my body that was both granular and intimate. (You try writing about ballet in a way that isn’t equal parts mechanical and overwrought.) Once you’ve gotten used to thinking of your body in this way, you then have to switch to understanding it on a macro level, putting all these pieces together to make whole movements that betray none of those technical aspects. You’re no longer a person broken down into tiny parts. You’re someone who can move decisively and even, when the situation calls for it, daringly. And, as opposed to writing a book or making a painting, you are the materials, and the art is not separable from you.

I have always liked dancers who can “travel,” flying across the stage with only a few movements, using even simple steps as excuses to roam and take up space. I had long legs as a teenager, and I wanted to be able to do that too. I would get in trouble, though, because I would take huge strides, stretching all my steps out unnaturally. You can tell when someone is doing this—they lead with their feet, and the top half of their body looks like it’s following after the bottom half, trying and failing to catch up.

How you successfully “travel” is you let your movement and your momentum come from your upper body. What people generally say is to imagine there is a string attached to your ribcage and that is pulling you forward. Ballet has a high center of gravity, which is to say that you are always being pulled upwards, your chest is expanding out and slightly up. This is what gives the illusion that dancers are flying or gliding.

Once you master this, you can almost propel yourself across the floor—perhaps dart is the more appropriate word, but it feels like propelling, you feel like a boat bounding along. I loved the grandiose way we would do this in shows: stepping out, claiming the stage, sweeping our arms out in front as if to say, look at me, see how I can take up this entire stage, see what I can do!

My mind has always seemed very loud to me—my thoughts race, ideas compete, the past weighs on me and the future worries me. When I danced I was focused, but my mind was quiet. I’ve heard people describe it as thinking with your body—I’m not sure I’d put it that way so much as that I was intensely conscious of every part of my body, not what it looked like but how it felt. I didn’t feel stuck in my head, or separate from my body. I was aware of the strength of my legs, the way a good pair of pointe shoes worked during certain steps, the need to keep the energy in my arms while also keeping them from getting tense, that particular shoulder muscle I struggled to engage.

At the height of my ballet education, I was dancing five to six days a week. Do you know how fit you are if you do this? I was so strong. I will never be that strong again. My legs especially felt so powerful.

This anecdote will probably only make sense if you have younger siblings,5 but I can remember that when I was lying on the couch reading and my little sisters would come over to bother me, I would just stick out my legs to keep both of them at bay. They would be giggling and slamming into me as hard as they could, and I wouldn’t even need to look up.

Even when I was standing still, I could feel the potential in my body, like ballet was always latent in my arms and legs. I knew that I could take charge of a space. I knew I was strong, that I was capable of a kind of movement that just a year or two prior would have seemed completely foreign. If before my body had seemed like a threat, now there was a different kind of potential to it.

I couldn’t help making sense of all this in religious terms. I had never really paid any attention to the doctrine of the resurrection of the body, the idea that in heaven your soul would be reunited with the same body you had on earth. It always seemed like a minor, kind of strange detail to fixate on. But I suddenly saw the appeal, why it might seem so urgent that you have your own body returned to you transformed, stronger, more glorious.

I think it’s helpful to make a distinction here between ballet and the culture that surrounds it. I am not saying that my experiences in dance were all uplifting or empowering. When I had just started with this dance school, our teacher had us do an exercise at the barre that was very quick and involved lots of tiny jumps, over and over. It was the kind of thing that makes your legs burn. As we walked back to the breakroom, there was some grumbling in the group: “She would make us do that, wouldn’t she? It’s so frustrating!” One of the girls turned to me and said, in a very friendly tone, “G. Marie, just wait—you’ll hate your calves soon! That kind of exercise will bulk up your muscles!” I rolled my eyes and nodded, but I was lost. I had thought that building muscles was the point of most of what we did at barre. It wasn’t until much later that I realized that these girls (who were all in seventh grade, eighth grade, or early high school!) saw ballet mainly as exercise and exercise mainly as something that should make you smaller—not stronger, and certainly not larger.6

It’s a grim way of looking at an art form. But it’s also not surprising that a bunch of girls in their early teens would think this way—that is how it had been presented to them. The thing is if you want to move, you have to take up space.

When I was thirteen, my dance teacher squeezed the upper part of my legs, sighed deeply, and announced to the room in an ominous voice that I had “over-developed quads,” a comment that instilled in me an abiding belief that there is Something Wrong with my thighs. It’s been over ten years since this happened, and I still think of it compulsively when I’m wearing shorts or tights. The great irony here is that, while I very much doubt that I had “over-developed” quads then, I definitely do not have any “over-developed” muscles now. If anything we have the opposite situation. And yet here we are, still worrying about it, sure that everyone else sees it.

Part of the reason why ballet could generally be freeing for me was that I fell through the cracks. I felt like an outsider in the group,7 and for that reason, it was easier for me to separate my good experiences in dance from the bad experiences interacting with ballet people, to ignore or even reject parts of dance culture that I might have otherwise taken for granted or internalized. I let a lot of the weirdest stuff I heard about food or being thin roll off me.

In addition, I was never that good at ballet, and no one was going to push me to fit some ridiculous standard, because it was clear I was not going anywhere.

I was also naturally on the thin side, so while there was the whole “over-developed quads” thing, no one really made fun of me, or guilt-tripped me about eating a normal amount of food, or made nasty comments about how I looked—I imagine this would have been very different if I had fit the mold less, which is, to put it mildly, awful. I said this at the beginning of the essay but it bears repeating—I don’t think that my experience is the common one.

If I felt like a bit of an outsider, I think it worked in my favor in the end. There are times as a student when it’s good to be on the outside, when you’ll learn more if you don’t trust what you’re told too much.

These days I try to maintain a neutrality regarding my body. When I notice it changing or aging, I do my best to view that nonjudgmentally and move on, treating any lingering thoughts as background noise. But the funny thing is that I didn’t feel neutral about my body when I danced. I loved my body, and I felt strong and dynamic.

Even if dance was showing me that there was more to the art world than books, I still wanted to read about ballet. Like everyone who danced in 2010s, I read Bunheads, a novel by former dancer Sophie Flack. There was a fair amount of ballet YA, much of which focused on eating disorders or murder, sometimes both. But I remember that I quickly became disappointed by what I read. If I was reading something aimed at anyone older than 12, the book was inevitably depressing. The plot usually revolved around ballet undoing a young woman’s understanding of her body. It always ended with the girl deciding to leave ballet.

I don’t mean this as a criticism—I usually enjoyed these novels, and while Bunheads is not a great book, its strength lies in Flack’s ability to replicate the casually unhinged way that dancers talk about food and their bodies. When asked in interviews about her own experience dancing at and getting let go from the New York City Ballet, Flack insisted she wasn’t angry. Like hell she wasn’t.8

It's good—not to mention just realistic—when authors include the not-pretty aspects of ballet. If you haven’t been in those circles, it can be hard to realize just how prevalent disordered eating is and how much it is actively encouraged by people in authority.

The only reason I was disappointed with these books was that I was looking for something that described what I had gone through. Ballet had transformed the way I understood my body for the better, but every novel was about the opposite experience.9 I got very excited when I found Clair De Lune by Cassandra Golds,10 a book about a girl who can’t speak but loves ballet. “Dance is a cruel God,” Clair thinks to herself at one point, “But that is because it was never meant to be a God.” I loved that line. It seemed true to me that there was something very cruel about ballet, but that this cruelty was not inherent to it. But even that book ended with the girl leaving—once she finds her voice, as I remember it, she doesn’t need ballet anymore.

I also stopped. I got sick of the drama, the way our teacher would find little ways to insult people, how much she seemed to dislike me during my senior year. It felt very high school, and I didn’t particularly want to take high school with me into college. And at the time, I couldn’t see a way to continue casually. Ballet was so all or nothing—I knew if I signed up for a weekly class, I’d be pressured to do more classes, to be in the show, to make the teacher like me, etc.

I’ve tried to go back to ballet occasionally. The last time, I showed up to an adult beginners/returners class, and the dance teacher refused to answer me when I asked for clarification about a step, just stared at me with her eyebrows raised, and then she was so mean to another student that she made her cry. Again, this was for beginners. I haven’t taken a class since.

I miss being good at it. I miss being bad at it. I miss the discipline, the slow exercises, the little breath you do with your arm before you start at barre. I miss the way I knew my body. I miss how powerful I felt.

Part of a good education is learning what things are for. Ballet is a cruel god, but then, we should all stop treating it like one. Ballet does not have the authority to stop you from eating or to decide that there is something wrong with your body. Ballet instructors have no special license to berate you or cause you pain. It’s just another art form—it should connect you to beauty. It can’t do that if it’s ruling over you.

One of my clearest memories of Maud, my first dance teacher, is a demonstration she would do sometimes for her gymnastics class. She would take a wooden folding chair and put one of her hands on the back and the other one on the seat. Then she would lean forward, putting all her weight on her arms, and lift both her legs in the air, raising them above her head. She would hold this position for a couple seconds, and then gracefully set her legs back down.

I wrote in an earlier essay that ballet teachers tend to be very performative. Maud was an exception to this—in her classes, you always felt like the students were the center of attention. But you could tell whenever she did this demonstration that she, a grandmother in her late 60s, was proud that she could so casually pull it off. Looking back, remembering how she always wore those fishnet tights and how she would brush off compliments from the moms with a little smile, I can see that she liked her legs, too, although again, she never seemed to be calling attention to herself. And I never once heard her critique the rest of her body. She never acted like it was bad to look like a grandma or have a belly. Why would she dislike her belly? Her core enabled her to do, you know, whatever you call that gymnastics thing.

I’m not saying that whether or not you like your body should be dependent on your ability to do insane core exercises in your late 60s (I will not be doing insane core exercises at any age), but I am saying that if you feel cut off from your body, dance, at least in theory, can help reinstate that relationship. You can love your body simply because it allows you to do cool things, to be strong, to learn a new way of moving through the world. Everything else is static.

On these aspects of ballet, I recommend season 2 of The Turning podcast.

In an essay I love very much (about a play I love very much),

writes: “Part of why Catholicism often represents ‘Christianity’ in the popular imagination is, I suspect, precisely this mixture of the alluring and the alienating, high aesthetic and kitsch, grandeur of the soul and obsession with everyday sins. Catholicism’s only close competition, in this respect, is snake handlers.” I have always loved this line, but every time I read it I always think, you’ve forgotten ballet! Ballet is very much a part of this competition!My sincere, public apologies to everyone I made feel bad for liking Percy Jackson.

Ballet class was also one of the few places where I didn’t feel intense pressure about my clothes and (lack of) makeup: I could just put on a leotard and tights in the required color, throw on some leggings, and I was set. I didn’t even have to wear a bra! This was very freeing for me.

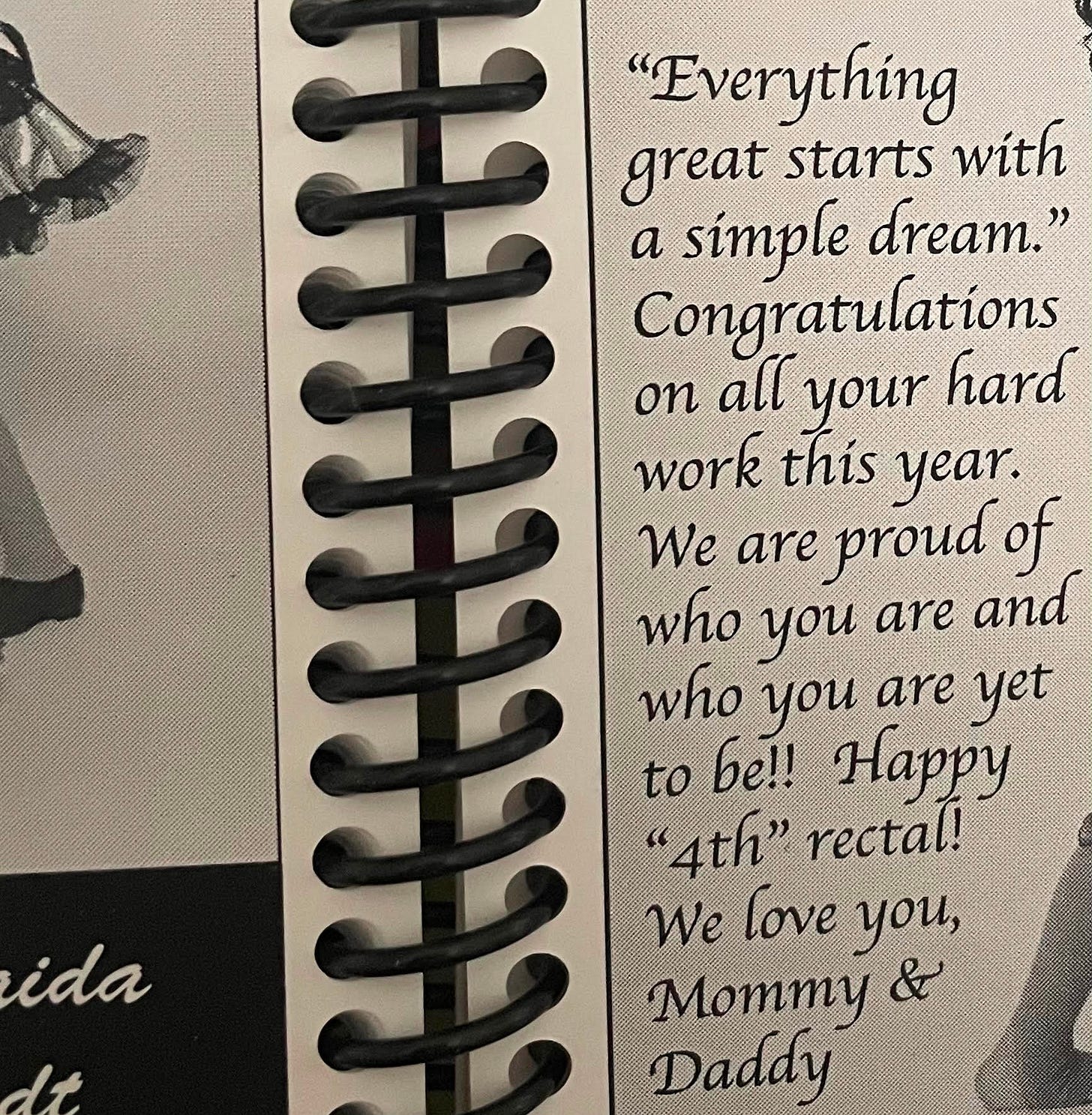

Speaking of siblings, my older sister Roxy once left this blurb for me in one of our dance programs: “G. Marie—always the last to laugh, brighter than a coal mine, and does the work of three men: Larry, Moe, and Curly.” I was like “Awwww thank you!! Who are Larry, Moe, and Curly?” Example #487 of my siblings being funnier than me.

These types of experiences have made me pretty anti “exercise” as a concept (I just wanna have fun), but I have really enjoyed

’s substack, and her essays (this one was very thought provoking) have challenged me quite a bit. I like the way she writes about lifting.For the most part I was not very close friends with the girls I danced with. They were generally a year or two older than me, and I don’t know that we had much in common. They spent a lot of time talking about the PSAT, a preliminary SAT test you take to be eligible for National Merit Scholarships, and their college decision-making processes. I’m not sure what I would have contributed, even if we had been in the same year.

One girl in particular took many of out-of-state trips to visit different campuses, and she talked about how boring it would be to stay in Pittsburgh. She ended up deciding to go to Carnegie Mellon University, which is in Pittsburgh (and, yes, named after Andrew Carnegie). Privately I expressed disdain for how wasteful this process was, but, to my discredit, I think I mostly just resented that she had so many choices.

She is featured in some of The Turning episodes and she is so good.

I still keep an eye out for this kind of writing, although I don’t look for it too actively.

’s recent essay was one of the few I’ve found where I felt like, yes, that was what it was like! (I have, admittedly, only read the first half as I am a bum and not currently in a position to be anyone’s paid subscriber.) I also enjoyed reading that she didn’t like Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfeild, because while I did like it as a kid I was also a little offended that it’s not really about ballet.Sophie Flack has said she is working on a memoir about moving to NYC in her teens to pursue ballet, and I really, really want to read that.

Author of the absolutely fantastic Museum of Mary Child, which at least 75% of my subscribers would love. The cover sucks, just ignore it.

have you read Toni Bentley's "Winter Diary"? it and her book Serenade are my two favorite things i've ever read about ballet (but i didn't do it as a kid… i did some tap and some gymnastics). she's kind of insane but in a good way!!

(also fair enough on the footnote… i was thinking of religions but you're totally right lol)

Not quite the same sort of thing: I was a very asthmatic child who didn’t really feel embodied (not sure I do even now lol) but playing wind instruments growing up helped expand my lung capacity and made me feel more positively toward my little lungs